At first pass, Amaluna would seem like a logical follow-up to Pippin; however, the big top Cirque du Soleil spectacle premiered in Montréal in 2012, just as Paulus was was preparing for her Tony Award-winning revival of Porgy and Bess.

Paulus reveals that during this time, her next Broadway triumph, the first-ever revival of the Stephen Schwartz-Roger O. Hirson musical Pippin, was never far from her mind, and that a "confluence of circus" helped bring the projects to life.

Playbill.com spoke with Paulus just as Amaluna pulled into New York City as part of its North American tour.

While this is inspired by The Tempest, Amaluna is not a text-based show. What kind of physical or visual vocabulary do you use to bring audiences into this journey?

Diane Paulus: I'm so glad you're bringing that up, because I think that sometimes Amaluna gets plugged as "the Cirque show with a story," and I want to say, "Let's just make it clear that it is still a circus show without a script." It's a circus-driven narrative. Guy Laliberté, who is the head of Cirque, wanted a big top show, which is kind of the bread and butter of Cirque — old fashioned, big top touring shows.

He wanted this one to be an homage to women; that was the kind of gauntlet put down, and I loved that idea. It meant two things: One, we were going to commit to casting a majority of women in the show, so it's 70 percent women artists and athletes; and two, they wanted a director to propose an idea that would be an homage to women. I'm not interested in doing a kind of women's agenda show. Some people were pitching me, "What if you do an act and they're all like women in high heels?!" I didn't think so. I thought, "Let's make great theatre and put in the center of it characters that are female heroines." So I started dreaming about Greek goddesses, Demeter and Persephone, a mother and daughter, the changing of the seasons and the spring, the rape of Persephone and what that mythologically means when a girl is kind of initiated into womanhood. Then I thought of Miranda, because I love Shakespeare, and I thought of a young girl in this brave new world and her experiencing life. Then I thought, "Well, if it's 'Prospera' and Miranda, then we could get the mother-daughter relationship there." I had also just directed The Magic Flute for the Canadian Opera Company, so I was living inside of Magic Flute and young love and initiation. So Amaluna is a mash up of Greek mythology, an homage to The Tempest and a little bit of Magic Flute. But to do the narrative, you first have an acrobatic skeleton, which is kind of a science in Cirque. Literally. there are acts that get coded red, yellow and green, which are different levels of excitement and skill. I spent a year in what they call "the creation rooms" in Montreal, with a story board on a wall, moving this act here and that act there, and I tried to frame the acts in a way that felt necessary.

| |

|

|

| Paulus and Randy Weiner |

DP: Yes. I also brought Randy [Weiner], who's my husband/partner. He's a dramaturge, and he started giving ideas on how to structure it. We were looking at women athletes from all over the world. I would fly to Montreal and sit in a room and watch hours of YouTube tapes: "Look, here's a woman shooting herself out of a cannon, one with a bow and arrow; and here's one with a machete, and two sisters from Spain who can balance on their head, and here's a contortionist from Africa!" [Laughs.] It was just looking, looking, looking, and I was having very visceral reactions to what I thought really celebrated women.

In the same moment I was developing with Randy and Fernand Rainville, the creative director at Cirque, what this story could be. We imagined a community of women on an island. What if there's Prospera and what if the Knights of the Round Table get called and then have different clans like the Valkyries and the Amazons? All of these different figures coming to an initiation of Miranda. Then we'd see an act in "the creation room," and I thought, "Oh, they could be the Amazons." You're constantly going back and forth and taking an acrobatic act, sticking it inside your narrative, and fitting the narrative to the acrobatic act. But what I think is different about this show is that there is real attention to the through line of characters. It's not, "Here's an act, and here's the next act!" There's a through line tracing through the whole show, with a goal that it will engage an audience to feel invested.

After something like Porgy and Bess, that was so about the text, was it liberating to approach this show that is not at all text-driven, or did that pose a challenge for you?

DP: It was more like directing a story ballet, which I grew up on because I grew up in New York as a little kid dancing in all those NYC ballets like Nutcracker and Coppélia, those great Balanchine story ballets. There are no words, and you're just using the body and physicality to convey the story. I love visceral theatre, and it was thrilling to be inside that full on. The hardest challenge in developing Amaluna was that you're dealing with acrobats, not actors, so the language is all acrobatic.

In Pippin it's half and half; you have a combination. But in Amaluna, it's all acrobatic, and I quickly learned that they can't do the tricks multiple times a day. They're training for up to six months. We were approaching the premiere, and I still hadn't seen some of the tricks done in a rehearsal because there are certain tricks that unless you have the adrenaline of an audience, they won't do the trick. It's too dangerous because, literally, you need the pressure of the moment. It's so virtuosic. These artists are like Olympic athletes. They would perform and then we'd meet with multiple coaches and choreographers for each act to watch the video. All the artists are there analyzing the video beat by beat, looking at what could be stronger. I would look at the tape with them, and there was a lot of directing through that video. I would ask, "Could you make that section shorter? That big trick you do there, I think it will be more powerful if you move it and it's the climax?" And it's an international situation. There are Russians, Chinese, French, so you are directing to multiple languages with interpreters. It's like the United Nations of a creation. [Laughs.]

| |

|

|

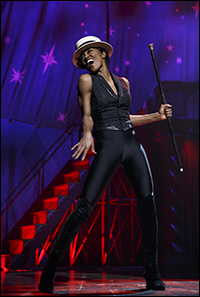

| Patina Miller in Pippin. | ||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

DP: I think that on Amaluna all of those athletes are performers. They have taken their skills and actually said, "Now I want to be in the entertainment business." So they are performing. So the idea that I was giving them acting notes and also notes on how to communicate and how to live emotionally — they all lapped it up. Everyone wants to be challenged and to grow as a performer. They were very open. We did the same character exercises I did with Audra McDonald and Norm Lewis and the cast of Porgy and Bess. Every single acrobat did one of those. They had to make individual presentations of who they were, what their name was, what their history was and why they were in this island. I think they were all terrified, but I made them do it because I wanted them to have a different purpose onstage. And that was very gratifying to work with.

Something about circus performers, which I loved, is that they're so used to being their own producer. They've made their act and then they've come to Cirque du Solei. You know, prior to Cirque, they've sewn their own costumes, they've done their own lights and so they're really invested in their acts. That's challenging if you want to change it, but also great, because they care. It's not like an actor saying, "Whatever you want to do, I'll do it." No, they care. It's like their intellectual property, their act. Viktor Kee, who is a world-class juggler in our show, plays a whole character based on Caliban, and it's tremendous what he does. I went home one night and found out that he had stayed one night until two or three in the morning working on the lighting on his own. You know, that doesn't happen in the theatre, that an actor says, "Excuse me! I'd like to finesse the lighting in my scene." [Laughs]. There's just a different energy there that I loved, and the community that Cirque built was really inspiring.

I was watching a bit of your "TEDxBroadway Talk," where you were speaking about Greek Theatre and that truly communal experience. From Hair to Pippin, you've really worked to break the fourth wall. Where did that impetus come from?

DP: In our moment of life now, what the theatre can provide is community. Theatre can provide ritual. It can provide a visceral experience. It's so pronounced, that divide of where you can get that and where you can't. And mostly our entertainment now, which dominates our lives, is interactive, but it's not. Of course, I see my kids viscerally entertained in "Dance, Dance: Revolution" and the TV, so I should maybe watch what I'm saying about what is visceral and what is not. But in this industry, people always say, "Ugh, the theatre is dead. What's the future of the industry?" I feel like now more than ever, the role of the theatre is clear in terms of what the theatre can provide. I'm just addicted to that part of the graph of what the theatre can be.

I think theatre can be many, many things. No one ever says, "I do sports." They say, "I play golf, I play tennis, I play basketball," and they're completely different. And what you experience as an audience member at a basketball game waving your foam finger at the foul line versus being quiet at a tennis match, you know, is completely different audience behavior. But in the theatre we say, "Oh, I'm in the theatre." What the hell does that mean? [Laughs]. There's a lot of different theatre out there and I think my interest as a director has been in the social experience, the ritual, our mission to expand the boundary of theatre and say, "Theatre doesn't have to be just this. It can be something else." I also feel that we go to the theatre to feel alive. And that's the quest in life, to feel present, because we spend all of our time planning and thinking about tomorrow. So it becomes, how do you get in touch with the present? Some people do it through sports or meditation. To me, theatre does that, or has the potential to do that. I'm always looking at how I can do that for an audience. That generous act of an audience of coming out to be at the theatre; how can I give them that? I want to meet them and say, "Yeah, you're here, you're alive."

| |

|

|

| Audra McDonald and Norm Lewis in The Gershwins' Porgy and Bess. | ||

| photo by Michael J. Lutch |

DP: Yes, to inspire colleagues or the next generation of theatre makers and audience to flex their muscles in different ways. I remember when we first did Donkey Show, it was not to say, "The only way you can do A Midsummer Night's Dream is in a disco with disco lyrics!" You don't, but theatre can look like that. That can be called theatre. We can be standing and dancing and that can be theatre. I think that's what I'm always interested in saying. Never assume that theatre has to look like this and be put in a certain box. Whatever I'm working on, I hope I'm continually pushing the boundaries, whether it's through the form, or the artists involved, through the content, through the physical life of the show, even where the show is. What I love about circus is, you know, you're in a tent. It makes you present, you're there, and it’s that architecture. Sometimes on Broadway you're somehow a little stuck with a certain architecture, so how do you make the architecture alive? Your work and your workload is so ambitious, and you're so ambitious. You're also the artistic director of the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, MA. Tell me about balancing the artistic needs of that institution and your work in New York and internationally.

DP: I took the job at A.R.T. because of that mission. The mission of the A.R.T. is to expand the boundaries of theatre through classics and the new work of tomorrow. When you run a not-for-profit institution, you have to live and die by the mission, and I knew I could live and die for that mission, because what I was doing as a director was directly aligned with that mission. It's a fit that feeds on itself because everything that I'm thinking about relates back to that mission, relates to how we raise money for the theatre, how we educate students about the theatre; it's like an endless feeder. And yes, A.R.T. is a regional theatre, but I think we're pushing the boundaries of what a regional theatre is. It's a new world. We're in the 21st century. We're developing a project right now at the A.R.T. that is with Aboriginal artists in Australia that will probably premiere in Perth, which is the furthest place in the planet from Boston. And you know what? We are in a global world, and a theatre can do that. So this idea of regional theatre with all its demands, is, to me, being exploded open by the gift of this mission of A.R.T. and the kind of incubation we've been able to do there. The fact that the work has found future life is just sort of the icing on the cake that we have shows traveling around the country right now and in New York.